Sunlight illuminates Portland Head lighthouse through storm clouds as a giant wave breaks over rocks in Maine.

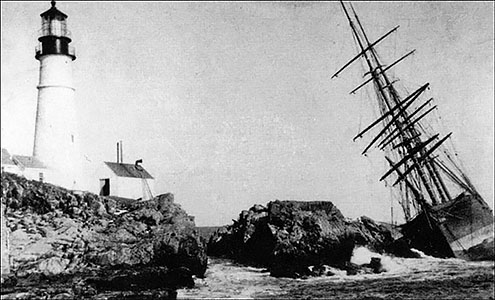

The Wreck of the Annie C. Maguire at Portland Head Lighthouse on a Stormy Christmas Eve, in 1886, in Southern Maine

One of the most memorable events at Maine’s Portland Head Lighthouse involved the Annie C. Maguire, shipwrecked next to the beacon on Christmas Eve in 1886. Joshua Strout was the lighthouse keeper at the time.

The Annie C. Maguire was a converted bark vessel built initially as a speedy clipper ship, named the Golden State, narrowly breaking sailing distance records on some of its voyages. As a clipper ship, it had a 30-year career involved in trade with China. Afterward, it was converted to a three-masted bark sailing vessel for carrying heavy cargo. Its owners, however, had run into financial difficulties and owed money to their creditors. A few days before Christmas Eve in 1886, a sheriff’s officer had received word that the Annie C. Maguire may be passing by or anchoring near Portland Harbor. He stopped by the Strout’s house next to the lighthouse and asked Joshua to keep an eye out for the vessel and to notify him if the vessel was sighted along Casco Bay.

On Christmas Eve in 1886, members of the Strout family were gathered together for the Christmas holiday at the keeper’s house. Joshua’s wife Mary had killed eight chickens a few days before baking her famous chicken pies. Joshua went up to the tower to remain on the lookout while everyone was settling in for the night, ready to enjoy Christmas dinner the next day. As the evening wore on, the winds were blowing but not gusting, and a mixture of rain and snow was falling over the area from a heavy storm raging offshore.

That same night on Christmas Eve, around 11:00 p.m., the Annie C. Maguire was headed for Portland Harbor en route to Quebec from Buenos Aires, Argentina. On board were two mates, thirteen crewmen, and Captain Thomas O’Neil’s family, including himself, his wife, and his teenage son, Thomas Junior. The captain had decided to wait out the impending storm in Portland Harbor. The waves were starting to get rough as the Annie C. Maguire started up along the coast. The temperature was pretty warm for that time of year, with rain falling along the shore, mixing in with occasional snow squalls. Suddenly, around 11:30 p.m., the vessel ran aground on the rocks nearly 100 feet from Portland Head Lighthouse. Captain O’Neil could not see the lighthouse in the heavy rains or possible snow storms and misjudged his location. He quickly had the crew take down the sails and lower the anchors to keep the vessel lodged on the rocks. He realized they had landed next to the lighthouse and knew they would be rescued shortly.

Joshua saw the wreck from the lighthouse tower and couldn’t believe his eyes. He ran into the keeper’s house and burst through the door, yelling, “All hands turn out! There’s a ship ashore in the dooryard!” The family had felt the ground shake and heard the noise from the impact of the vessel slamming into the nearby rocks. As his son Joseph quickly put his clothes back on, he ran out the door and was shocked to find the rather large vessel on the rocks listing to one side nearly 100 feet from the lighthouse. Keeper Strout’s wife, Mary, grabbed a blanket, cut it into strips, and soaked them in kerosene. She lit them as torches to illuminate the area for rescuing the crew. Joshua and his son Joseph rigged an ordinary ladder as a gangplank between the waves and rocky ledges that separated them from the wreck. One by one, Joshua and Joseph helped each survivor over the makeshift plank to the warm safety of the keeper’s house. They rescued all eighteen people safely while the ship lay wedged on the rocks.

When they reached the keeper’s house, the survivors, freezing from the icy waters, had all their drenched clothing cut off and removed and were given warm blankets and clothes. Mary soon had hot coffee and food for the survivors and helped in rubbing their hands and feet with warm kerosene and glycerin. They found that the crew had been on food rations of salt beef and macaroni for weeks, mixed in with lime juice to keep them from getting scurvy, and were quite famished. After they were provided a Christmas dinner the next day, consisting of Mary’s famous chicken pies, they loafed around for three more days consuming any food left. The Strout family, although only able to manage a plateful apiece of the delicious delicacies, felt it was their duty to oblige their unexpected guests. Keeper Joshua Strout did try to convince the crew that they were not at a lifesaving station, where there was plenty of food for large groups, but at a lighthouse station, where food was limited. This seemed to fall on deaf ears as the survivors continued to stay on and fill their bellies with any food they could find. Captain O’Neil and his family were very gracious to the Strout family and appreciative of their efforts, although the Captain had problems managing the angry crew. Strout still felt obliged to help his guests, which is a valuable testament to the kind character of this lighthouse keeper.

The following morning on Christmas day, the deputy sheriff, notified of the wreck, came to claim the ship and put Joshua Strout in charge of salvaging anything from the wreck for the creditors. When two cases of scotch whiskey were brought into the house, the selfish crewmembers drank the contents at once, got very drunk, and beat up their ship’s cook for the meager rations they were served during the latter part of the trip. The scuffle was broken up before anyone was hurt badly. Joshua Strout’s son, Joseph, kept a spear-like device from the ship as a souvenir, probably used to fend off the local natives at a remote port that may have been trying to board the ship.

Because the ship was so beaten up, the creditors received only $177 at auction. In trying to serve the angry creditors, the sheriff searched the ship’s sea chest for special papers and cash but found nothing.

Just over a week later, on New Year’s Day of 1887, another storm destroyed what was left of the Annie C. Maguire. The crew of the ill-fated vessel had been discharged a few days earlier and sent home by the British Vice Counsel. Years later, it was discovered that the captain, with the help of his devious wife, had ransacked the chest and carried the cash, papers, and other items of value in her hatbox during the rescue.

When Joshua Strout retired as Maine’s oldest lighthouse keeper in 1904 at the age of 79, his son Joseph, already an assistant keeper, was appointed as the next-generation keeper at Portland Head Lighthouse. He had a positive reputation like his father and was affectionately called “Cap’n Joe” by the locals and mariners alike. The family also had a parrot named Billy for many years. The parrot learned that when inclement weather was coming, it would shout, “Joe, let’s start the horn. It’s foggy!”

Joshua Strout passed away a few years later at the age of 81. The Strout family, a combination of father and son, were keepers of Portland Head Lighthouse for 59 years from 1869-1928. When the assistant keeper position was traditionally promoted to John Strout, Joseph’s son, on his 21st birthday in 1912, he became the third generation Strout to serve in a government position at Portland Head Light.

It was on his birthday that John Strout decided to paint an inscription to commemorate the location of where years ago the Annie C. Maguire had wrecked on the rocks close to the lighthouse. He had to chip a large portion of the stone away to create a flat surface to paint. After mixing mortar, sand, and some paint, he painted the words “In Memory of the Ship Annie C. Maguire, Wrecked on this Point Christmas Eve, 1886.” He had a wooden cross placed on top of the rock as well. The wooden cross has long since washed away along with the original painting, but the inscription has been periodically renewed and repainted over the years. It has evolved into a more brief inscription reading “Annie C. Maguire, Shipwrecked Here, Christmas Eve 1886,” which displays today for residents and tourists alike.

The Strout family of four generations served a total of 128 years as lighthouse tenders, with over 100 years of combined service between family members, including Joshua’s mother’s tenure as a housekeeper at Portland Head Lighthouse.

Exploring Portland Head Lighthouse and Grounds

The lighthouse is situated over picturesque rocky cliffs inside Fort Williams Park, and plenty of trails cover over 40 acres. You can also visit the fort, play around the beach nearby, hike around this area, picnic, and even go kite flying. For those that want a unique experience, try a narrated historic tour aboard Maine Duck Tours where you can ride these amphibious vehicles through Portland and into the water as they pass by Portland Breakwater and Spring Point Light. Many other boat tours are leaving the Portland waterfront, where some pass by Portland Head Lighthouse or the two other beacons nearby, Spring Point Lighthouse and Portland Breakwater Light, also known as “Bug Light”.

Have a wonderful holiday season, and if you can visit Portland Head Lighthouse, look for the painted inscription to commemorate one of the region’s most famous rescues. You’ll also find the Portland Head Museum next to the lighthouse to learn more about Maine’s oldest lighthouse and discover all kinds of marine artifacts and historical documents.

Here are some of my favorite photos of Portland Head Lighthouse.

Enjoy!

Allan Wood

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships: Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England. In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships. Stories involve competitions, accidents, battling destructive storms, acts of heroism, and their final voyages.

Available in paperback, hard cover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

My 300-page book, Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, along with plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions you can explore. These include whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours and adventures, unique parks and museums, and even lighthouses you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of shipwrecks and rescues. Lighthouses and their nearby attractions are divided into regions for weekly and weekend explorers. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

My 300-page book, Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England: New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont provides special human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses, like the one above, along with plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions you can explore, and tours. Lighthouses and their nearby attractions are divided into regions for weekly and weekend explorers. Attractions and tours also include whale watching tours, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours and adventures, unique parks and museums, and lighthouses you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography, do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation