Thanksgiving 1898: Perfect Storm Sinks the Steamer Portland and Becomes Known as the “Portland Gale”

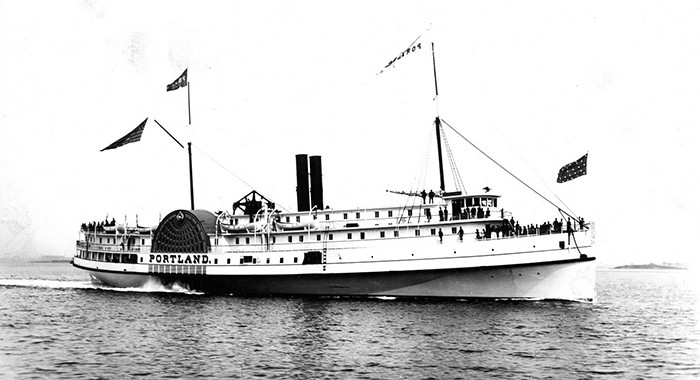

Perhaps the most famous of New England ship disasters of the 19th century was the sinking of the steamer Portland. It was built in 1889 and carried passengers and cargo between Boston and Portland, Maine, during the heyday of the steamship era. At over 280 feet long and 42 feet wide, the Portland was one of New England’s largest and most luxurious steamers, accommodating up to 800 passengers.

On November 24, 1898, Thanksgiving Day started clear and cold over the New England coastline. Still, as the weekend progressed, two storm systems, one from the Great Lakes and the other from the South, would come together over the New England coast, producing one of New England’s worst storms. On Saturday, November 26, 1898, it is believed that Captain Hollis Blanchard and his superiors knew a snowstorm from the South with gale-force winds was approaching that day. No one was prepared, however, for the intensity or duration of the storm. Captain Blanchard continued to prepare the steamer Portland for its run from Boston to Portland. With snow starting to fall that evening, over 175 passengers enjoyed Thanksgiving weekend, boarded the Portland, and left Boston Harbor at 7 p.m. The exact number of passengers was never known, as all records were only kept aboard the ship.

Later that evening, the two storms collided over the New England coast, a kind of “perfect storm system”, becoming one of the worst recorded nor ’easter storms in history. Several ships reported seeing the Portland pitching in the rough seas in their own battles to stay afloat that night. The ship likely got no farther than Cape Ann along the Massachusetts North Shore before being driven off course, turning east to avoid the rocky coastline. Keeper Whitten of Thacher Island Twin Lights, near Rockport, Massachusetts, claimed to have seen the Portland from the lighthouse’s north tower about a mile off Thacher Island before she was out of sight in the storm.

At 11 p.m. on Saturday, according to the schooner’s captain, an account was later given of the Portland almost colliding with the fishing schooner Grayling, one of the vessels that had survived and rode out the storm at sea.

The winds increased to hurricane force, forcing the steamer Portland further and further south until, by Sunday, November 27th, she was floundering off the coast of Cape Cod. The ship’s lights probably failed, and launching life rafts would have been nearly impossible. With such high winds and huge waves, the captain would not have been able to turn around without getting capsized by the heaving seas.

By Sunday evening, bodies and wreckage from the Portland began washing up between the Race Point and Peaked Hill Bars Life-Saving Stations on Cape Cod. It was believed the ship sank on Sunday, Nov. 27, around 9 a.m., because watches recovered with the bodies stopped between 9 and 10 o’clock. It was still unknown whether the Portland capsized, broke apart, exploded, or collided with one of the other lost ships. It was also unclear how many passengers were aboard since the only passenger list was on the ship. As the days followed, newspapers printed lists of those thought to be on board and descriptions of bodies that had washed ashore.

The storm lasted over 30 hours and packed coastal wind gusts of 100 mph. The storm buried much of New England in 2 feet of snow, washed away coastal buildings and destroyed neighborhoods, sank or grounded hundreds of boats and ships, and killed more than 400 people. The blizzard had destroyed telegraph and telephone lines from Cape Cod, and it buried or washed out railroad tracks. Finally, news started to get out about the fate of the Portland.

With no survivors from the tragedy, later accounts would print stories that the Captain had sailed against the orders of the company’s general manager because he was eager to get home to Maine for a family reunion. Other accounts suggested that the shipping line, not wanting to strand holiday passengers in Boston, ordered the Captain to sail against his better judgment.

The storm of 1898 was one of the worst storms New England had ever seen. Over 140 ships were lost in the storm, but with the sinking of the Portland, with nearly 200 crew and passengers perished, the Gale of 1898 has been known as the “Portland Gale.” To this day, it is not known precisely how many passengers were aboard or who they were. The only passenger list was aboard the vessel.

As a result of this tragedy, as with most, sometimes positive things come out to avoid the same issue. New regulations were established afterward for all passenger ships to leave a second list of passengers ashore before they depart and a list to be sent to their destination. This practice still continues with traveling ships today.

In 1989, the American Underwater Search and Survey Ltd., a Cape Cod marine search-and-survey company using specialized sonar technology, announced it had found the Portland‘s resting place, confirmed in part by the discovery of the large metal “walking beams,” which connected the steam engine pistons to the paddle-wheels on either side of the steamer. News of the discovery was not publicized for many years to protect the site. Finally, with all information verified and confirmed, they gave the coordinates of the wreck to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration since the Portland was within the protected Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, which prevents divers and other ships from exploring the vessel without expressed permission by the NOAA. The ship lies undisturbed at a depth of about 400 feet some miles outside of Gloucester, Mass. The NOAA manages the sanctuary and uses high-tech equipment to photograph and record the wreck’s location.

Travel safely and enjoy your Thanksgiving with those you love.

Allan Wood

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships: Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England. In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies. They measured longer than a football field! This book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships, from their initial launches, battling destructive storms, to their final voyages.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

My 300-page book, Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, provides special human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses, along with plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions you can explore. These include whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours and adventures, special parks and museums, and even lighthouses where you can stay overnight. Like the one above, you’ll also find many stories of shipwrecks and rescues. Lighthouses and their nearby attractions are divided into regions for weekly and weekend explorers. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

My 300-page book, Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England: New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont, provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses, with lots of information about indoor and outdoor coastal attractions you can explore and tours. Lighthouses and their nearby attractions are divided into regions for weekly and weekend explorers. Attractions and tours also include whale watching tours, lighthouse tours, windjammer sailing tours and adventures, special parks and museums, and lighthouses where you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

You’ll find more details of the “Portland Gale” story and over 50 others in my book New England Lighthouses: Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales. This image-rich book also contains vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous artists of the Coast Guard.

You’ll find this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores like Barnes and Noble.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, Support The American Lighthouse Foundation