Strange Collision of the Only Two Six-Masted Sailing Vessels in Existence

by Highland Lighthouse on Cape Cod

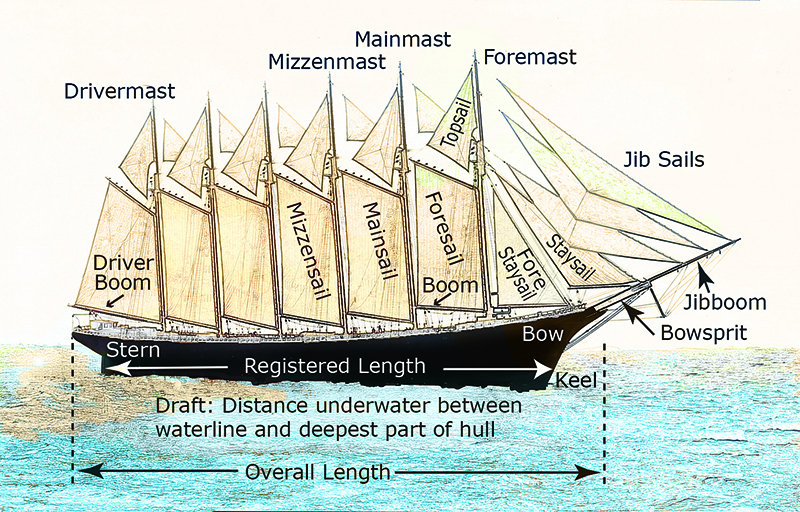

The first six-masted schooner, the George W. Wells, was built at the Holly M. Bean Shipyard in Camden Harbor, Maine. The giant vessel measured 303 feet along her registered keel length at the waterline, 48 feet wide, and 23 feet deep to hold over 5,000 tons of cargo. When fully loaded, her draft, or the underwater distance between the waterline and the deepest part of the hull, would be 24 feet. When the George W. Wells had her original launching on August 4, 1900, temporary masts were used instead of permanent masts, which weren’t ready for installation. The purpose was to beat the scheduled launching of the Eleanor A. Percy, which the owners from the Percy & Small Shipyard in Bath, Maine, had initially planned to become the “first” six-masted schooner.

The second and the new largest schooner, the Eleanor A. Percy, was launched on October 10, 1900, two months after the George W. Wells. She was the largest of all wooden sailing ships, measuring a 323-foot-long hull with an overall length of 347 feet over the deck from stem to stern and a breadth of 50 feet. She was heavy and could carry over 5,500 tons of cargo. Newspapers started referring to her as the “queen” of all sailing ships.

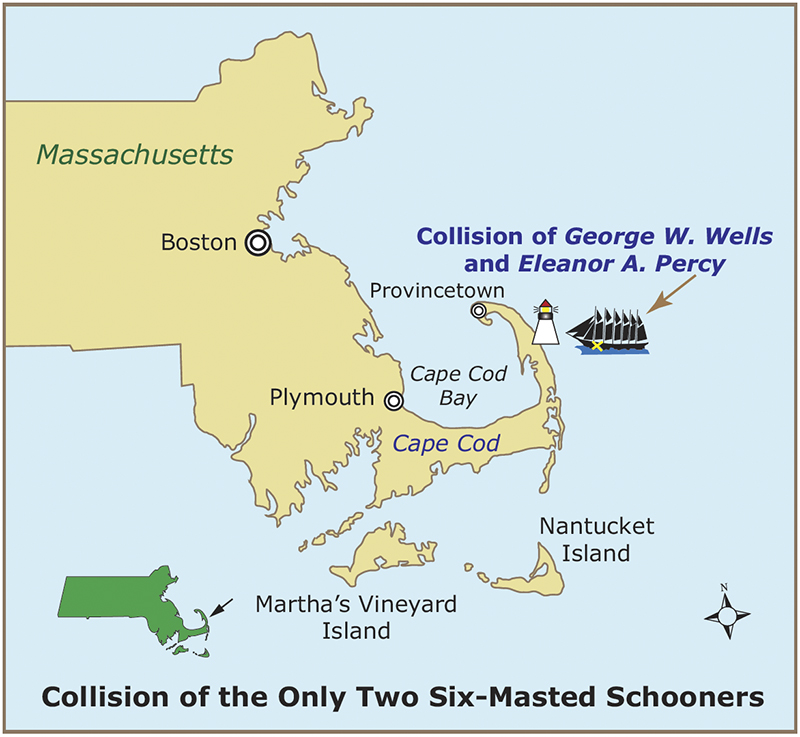

Due to the massive size of both vessels, maneuvering them was sometimes challenging, especially with a full cargo load. Most merchant ships traveled the same shipping routes, and many would sail near one another. Maneuvering giant four and five-masted schooners was challenging, and collisions or wrecks sometimes occurred. Many collisions were usually the result of human error, like a crew member in charge as the lookout neglecting his duties. What is bewildering to many historians and mariners is that the only two six-masted sailing ships in existence at the time, the George W. Wells, and the Eleanor A. Percy, ended up colliding together off the coast of Cape Cod in Massachusetts. They were the largest wooden sailing ships in the world.

On a clear, moonstruck night on June 29, 1901, the George W. Wells collided with the only other six-masted ship, the Eleanor A. Percy, off northern Cape Cod. The George W. Wells was sailing light with the wind out of Boston Harbor. She had just rounded Provincetown on Cape Cod and was heading south to Newport News, Virginia, for another load of coal. Captain Arthur Crowley brought his wife and children along for the journey. Under full sail, the Eleanor A. Percy was heading northward with 5,400 tons of coal for delivery to Boston and was traveling at a good clip of about 10 knots.

Around 10:00 p.m., a few miles off Highland (Cape Cod) Lighthouse, sailors on the George W. Wells spotted the lights of the Eleanor A. Percy about three miles away on that clear Saturday night. As the giant schooner continued towards them, they watched the lights come closer and realized their ship was in danger. Before 10:30 p.m., the crew started shouting at the larger six-master as they braced for impact, and then the Eleanor A. Percy plowed into the port side near the middle of the George W. Wells. The force was so great that the massive port anchor of the larger ship, weighing nearly 8,000 pounds, was thrust into the side of the George W. Wells as the crew fell onto the deck. Like a wrecking ball, the anchor smashed through the hull, creating a huge hole where it lay lodged deep inside. Both vessels remained entangled together for nearly half an hour before breaking away, causing each to sustain more damages where they reconnected, as extensive repairs were deemed necessary.

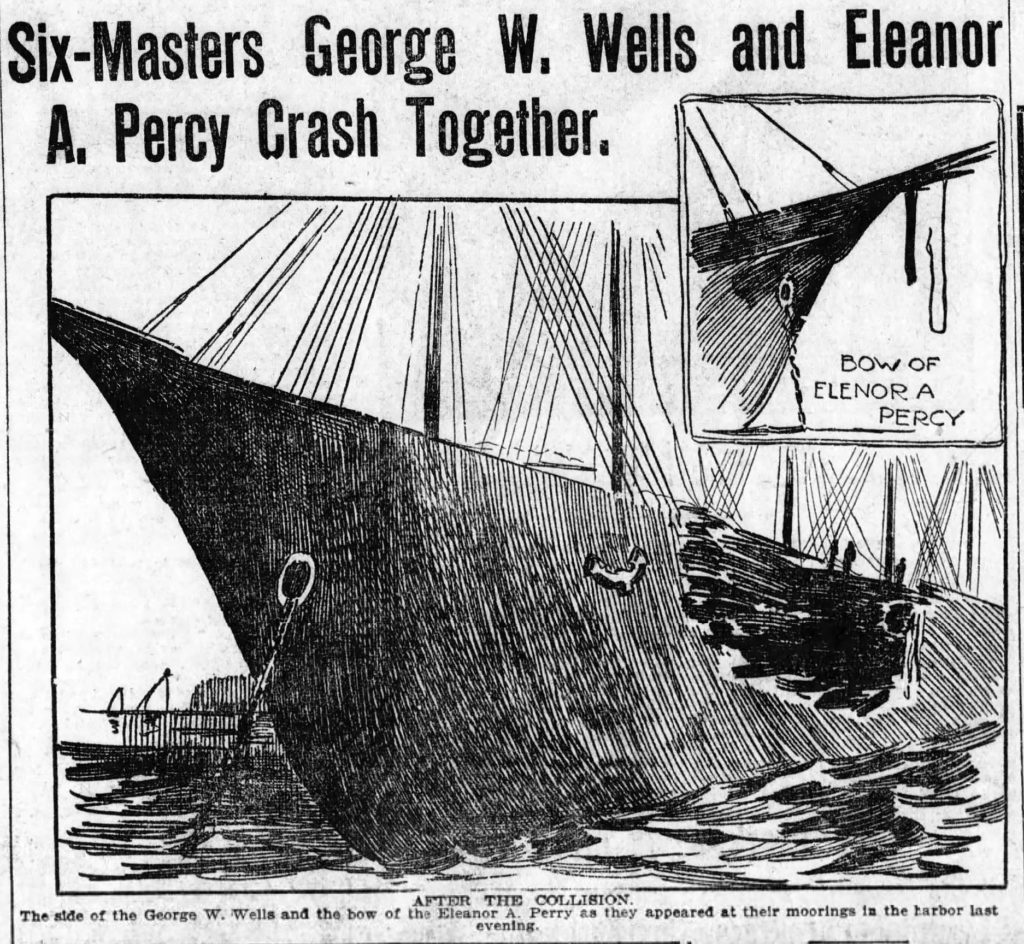

Nearly 30 feet of planking was crushed inward on the George W. Wells as far as the galley, destroying one side. The hole was within six feet of the waterline, between the main and mizzen rigging (by the second and third masts) near the front third of the ship. In addition, part of the mizzenmast had been sheered away, a couple of booms snapped, and the mainsail ripped away. A considerable bulge appeared on the opposite side of the impact area, and cracks were displayed back to the poop deck, indicating the severity of the shock from the collision. Luckily, the George W. Wells was traveling without cargo; otherwise, the gaping hole could have sunk her.

Captain Lincoln Jewett commanded the Eleanor A. Percy and was unaware of the impending collision. The helmsman of the largest sailing vessel did not alter her course, as he received no calls from the lookout to make any changes until she was too close to the George W. Wells to avoid the crash. The mate of the Eleanor A. Percy was assigned lookout duty before the collision as Captain Jewett went below. He either did not see the George W. Wells approaching or was seriously misjudging the distance between the two vessels, their course, or their speed. The front headgear equipment with the bowsprit and jibboom of the Eleanor A. Percy was destroyed as all her headsails except for her foresail were torn to pieces and rendered useless. The force of the impact was so great she broke off the bowsprit base, a solid piece of hardwood measuring three feet in diameter. Huge gouges displayed where her anchor had torn across the bow at impact. Much of the planking in the front would need to be removed and replaced, along with most of the destroyed frontal equipment. Miraculously, no one suffered injuries from either ship in the collision.

Although there was a lot of confusion between crew members initially, both captains assessed their vessels and concluded that neither was about to sink. That night, the crews of each ship worked tirelessly to remove wreckage to prepare to sail that early Sunday to return to Boston Harbor. Both schooners reached Boston Harbor amongst a crowd of curious reporters. Neither captain would say much in front of reporters, and neither lashed out at the other as to who was at fault, as each had the utmost respect for the other.

Upon reaching Boston Harbor, each scheduled a tow to Bath, Maine, for about seven weeks of extensive and vital repairs. Upon arrival in Maine, work crews were split into teams, as one group worked on the outside while another worked on the inside of each vessel. The site of both ships at their dry docks became quite a tourist attraction for visitors to see these two marvels of shipbuilding in one location. Boats traveled along the Kennebec River to give onlookers a close look at the two ships, providing a waterside view. Crowds gathered daily, and traffic became congested along the roadways during the weekends as tourists stopped to see both colliers.

Removing the 8,000-pound anchor still lodged inside the George W. Wells proved quite challenging for workers on the dry dock. The anchor was stuck fast, about 25 feet inside the hole it had created. Workers brought a team of horses in to pull the anchor out successfully.

The shipyard estimated that it would cost over $25,000 to repair both ships, including services, fees, and towing (the cost would be around $900,000 today). With estimates provided, the owners of the Eleanor A. Percy admitted fault and paid for all repairs. Neither ship had insurance, as the owners avoided the high costs and preferred taking their chances.

Books to Explore

The Rise and Demise of the Largest Sailing Ships: Stories of the Six and Seven-Masted Coal Schooners of New England. In the early 1900s, New England shipbuilders constructed the world’s largest sailing ships amid social and political reforms. These giants were the ten original six-masted coal schooners and one colossal seven-masted vessel, built to carry massive quantities of coal and building supplies and measured longer than a football field! This book, balanced with plenty of color and vintage images, showcases the historical accounts that followed these mighty ships. Stories involve competitions, accidents, battling destructive storms, acts of heroism, and their final voyages. You’ll find more details in the story of the strangest collision mentioned above in this book.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and as an eBook for all devices.

Book – Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions in Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts

My 300-page book, Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Southern New England: Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 92 lighthouses. You can explore plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions, including whale-watching excursions, lighthouse tours, parks, museums, and even lighthouses you can stay overnight. You’ll also find plenty of stories of hauntings around lighthouses.

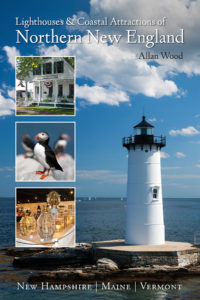

My 300-page book, Lighthouses and Coastal Attractions of Northern New England: New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont, provides memorable human interest stories from each of the 76 lighthouses, along with plenty of indoor and outdoor coastal attractions you can explore and tours. Attractions and tours include whale watching, windjammer sailing tours, lighthouse tours, unique parks, museums, and lighthouses you can stay overnight. There are also stories of haunted lighthouses in these regions.

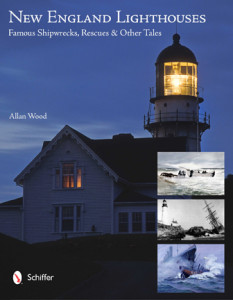

My book New England Lighthouses: Famous Shipwrecks, Rescues & Other Tales contains over 50 stories. This image-rich book also contains vintage images provided by the Coast Guard and various organizations and paintings by six famous Coast Guard artists.

You’ll find this book and the lighthouse tourism books from the publisher Schiffer Books or in many fine bookstores like Barnes and Noble.

Copyright © Allan Wood Photography; do not reproduce without permission. All rights reserved.

Join, Learn, and Support The American Lighthouse Foundation